What the heck is going on?

This all kicked off on Wednesday with SentinelOne’s release of a post that looked at a campaign dubbed “Smooth Operator”, which essentially found that the 3CX Voice Over Internet Protocol (VOIP) desktop client – used by some 600,000 companies worldwide and over 12 million daily users – had been compromised with a malicious update.

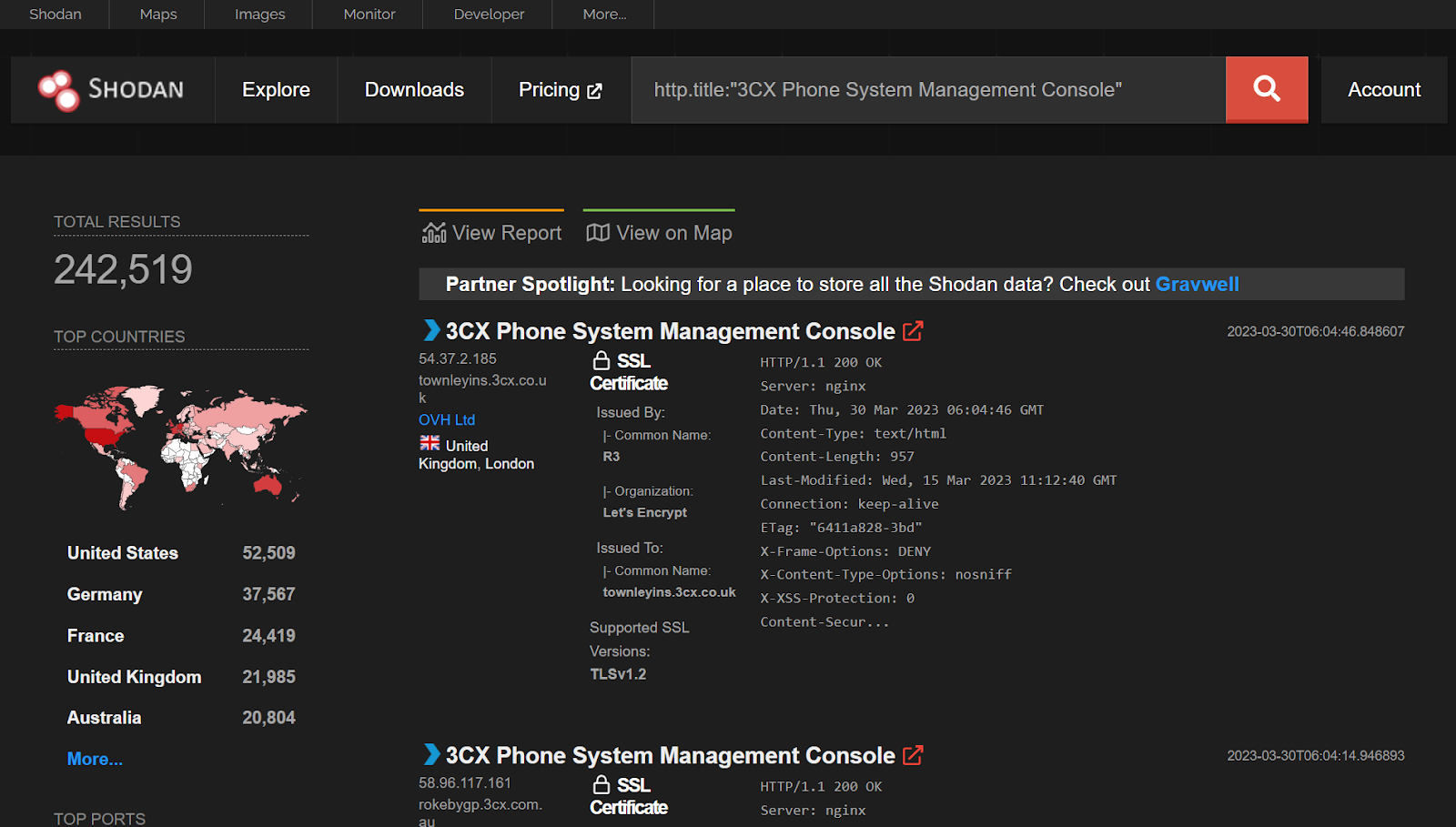

Moreover, Huntress Labs found 242,519 internet-exposed 3CX phone management systems as of the 30th March, and a further 2,783 instances in their customer networks running the trojanized software.

What can I do?

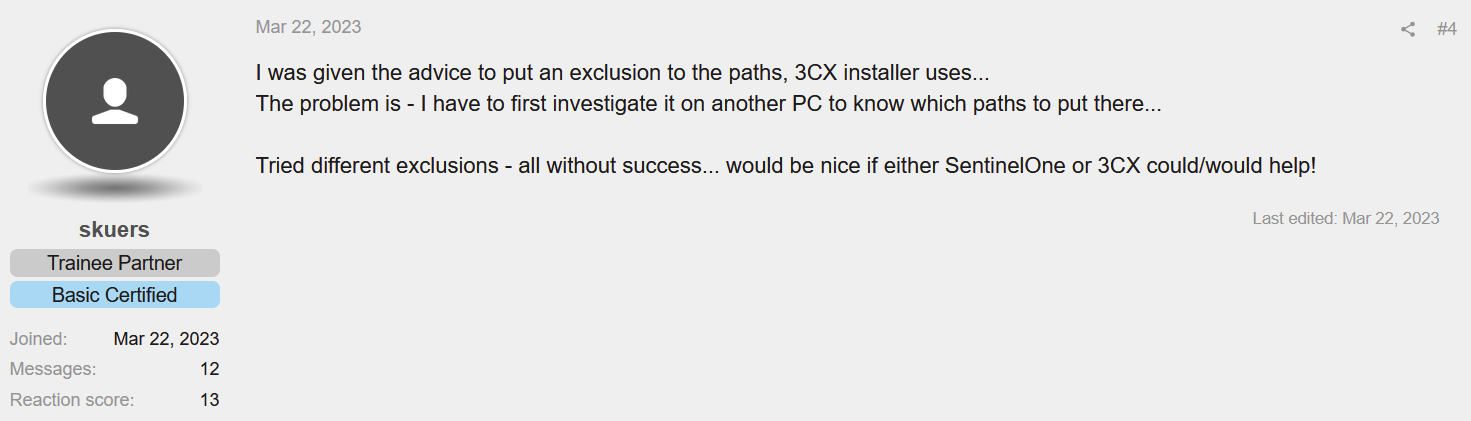

Well for one – ensure you’ve removed any exceptions that might have been created for the application.

The compromised software has been assigned CVE-2023-29059, and impacts the following versions on Windows and MacOS:

- Windows: versions 18.12.407 and 18.12.416 of the Electron Windows application shipped in Update 7, and

- Versions 18.11.1213, 18.12.402, 18.12.407, and 18.12.416 of the Electron MacOS application.

Immediately uninstall any affected versions of the product, and perform hunting using IOCs noted in the articles in the Further Reading section at the bottom of this post.

Florian Roth and his team have also shared several Sigma and YARA rules to help identify compromised files that were leveraged in the attack.

How did this happen?

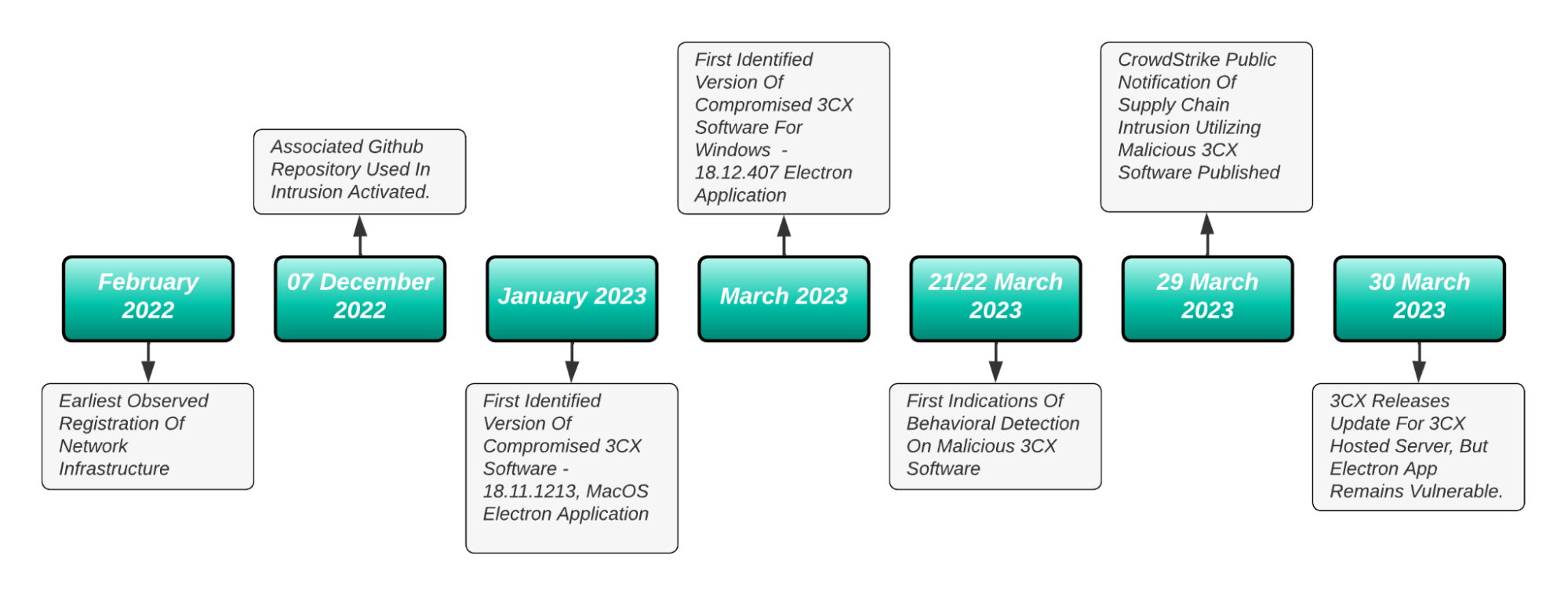

Customer reports of the trojanised application being quarantined by antivirus products first began surfacing the week prior, on the 22nd of March, though SentinelOne have reported observing activity as far back as March 8th.

Analysts at Volexity have found the domains and web infrastructure used in the attacks were registered as early as November 2022, and infrastructure used by the Windows variant were activated on December 7th, 2022.

Huntress Labs have taken it one even further, having found network infrastructure being established as far back as February 2022:

Whose supply chain was hit?

ReversingLabs have done some great analysis of the potential origin of this attack, pointing to either a compromise of the 3CX development pipeline (a la SolarWinds) or a malicious upstream dependency, the kind we often see impacting package repositories like PyPI, Maven, or npm.

3CX were quick to point fingers at ffmpeg – the upstream code supplier for the trojanized ffmpeg.dll binary – but they clearly weren’t in the mood for it and told 3CX to double-check their homework:

There have been several incorrect reports that FFmpeg has been involved in the distribution of malware.

FFmpeg only provides source code and the source code has not been compromised. Any “ffmpeg.dll” that has been compromised is the responsibility of the vendor.

— FFmpeg (@FFmpeg) 4:44 PM ∙ Mar 30, 2023

That said, Volexity researchers are right to point out that in order to have trojanized the software’s updates so effectively, the actors would have lingered in 3CX’s network for some time – sufficient enough to “develop an understanding, access, and malicious code for the development-update process of the company”

3CX have engaged Mandiant to conduct an investigation, which is ongoing as of the time of writing.

How does the attack work?

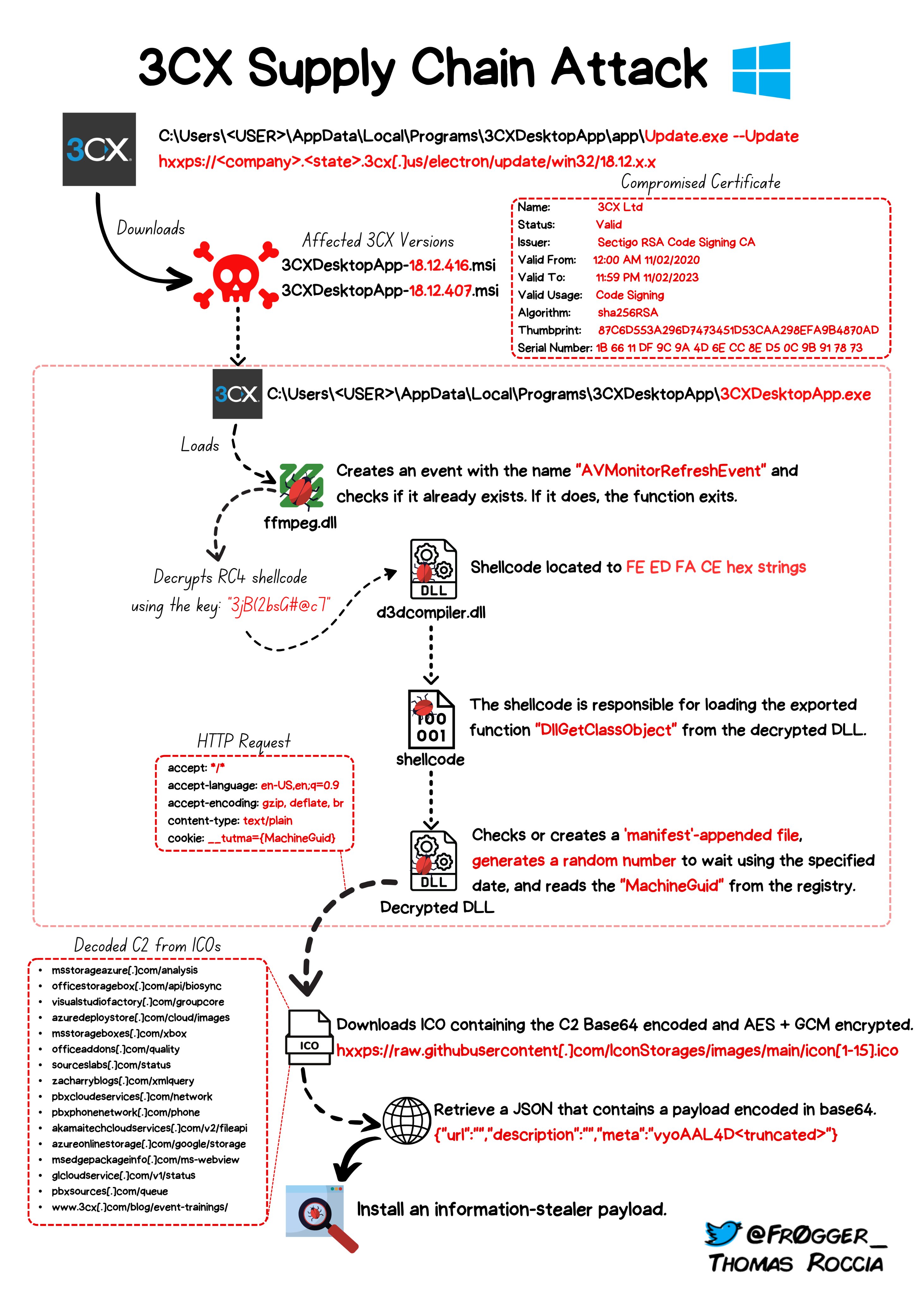

A trojanized update which was sent out to customers included a modified and malicious version of the legitimate ffmpeg.dll and d3dcompiler.dll binaries, which then retrieved an obfuscated and encrypted .ICO file from an attacker-controlled Github repository.

This subsequently dropped an info-stealing payload which Volexity have dubbed “ICONICSTEALER”. The 64-bit DLL was compiled on March 16, and is “designed to collect information about the system and browser using an embedded copy of the SQLite3 library.”

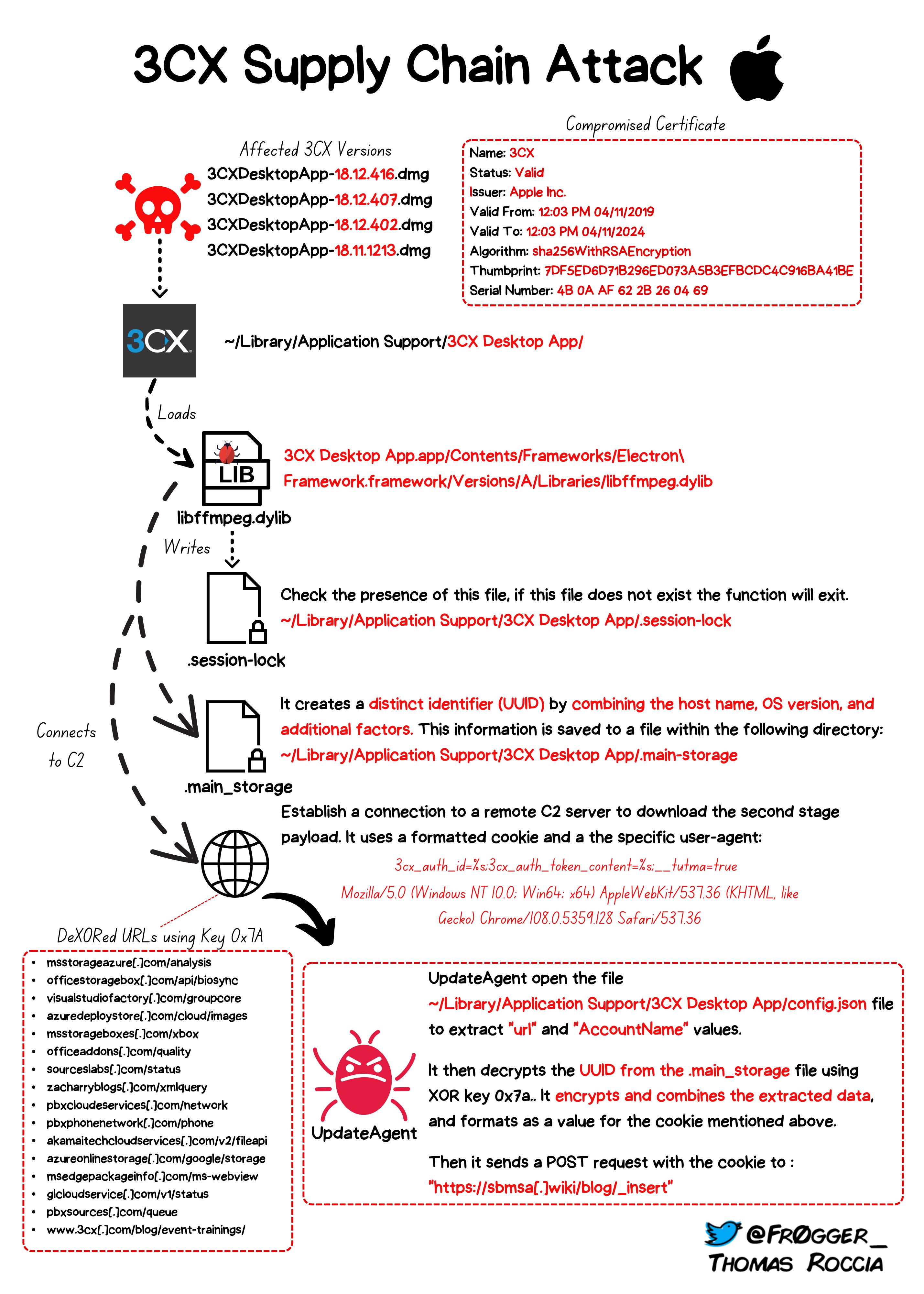

MacOS Execution Chain

A malicious update was also issued for the MacOS version of the 3CX installer, and it appears to have actually pre-dated the Windows attacks, with the earliest vulnerable version – 18.11.1213 – being deployed in January this year.

You can find a more detailed analysis of the execution chain in Patrick Wardle’s blog, but for a quick overview, Thomas Roccia (a.k.a @fr0gger_) has you covered:

Signed =/= Trusted

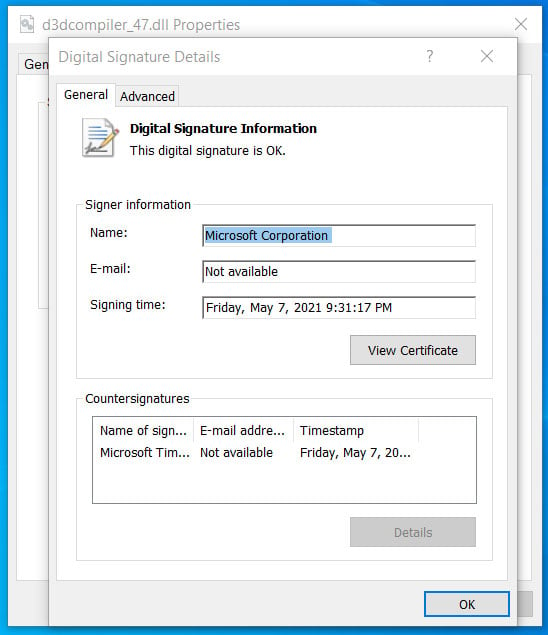

Notably, ReversingLabs reported in their analysis of the Windows sample that they “identified signatures in the appended code pointing to SigFlip, a tool for modifying the authenticode-signed Portable Executable (PE) files without breaking the existing signature.”

This was elaborated on by Will Dormann, who pointed to its apparent use to abuse a 10 year old flaw – CVE-2013-3900 – classed as a “WinVerifyTrust Signature Validation Vulnerability.”

The vulnerability would allow an attacker to append content to the authenticode signature section (WIN_CERTIFICATE structure) of a signed executable – without invalidating the signature.

While a fix was issued back in 2013, Microsoft made it opt-in, as it could break functionality of legitimate apps such as Google Chrome, which modifies the Authenticode signature as part of denoting if diagnostic logs are meant to be collected and sent.

The result? This was abused to append a malicious payload to a usually legitimate DLL signed by Microsoft named d3dcompiler_47.dll, with the signature left intact and incorrectly marking the file as being unaltered and verified by Microsoft.

This is significant as it allowed the attacker to bypass basic file-signing checks by both automated security controls and L1 security analysts. It would have also played a part in influencing system admins to dismiss EDR alerts as false positives, and to create security exceptions so the apparently untampered software could continue to run.

So, who did it?

CrowdStrike have attributed the attack to a group they track as Labyrinth Chollima, a DPRK-aligned actor with form conducting cyber espionage, cryptocurrency theft and destructive attacks. Their analysis found “the HTTPS beacon structure and encryption key match those observed by CrowdStrike in a March 7, 2023 campaign attributed with high confidence to DPRK-nexus threat actor LABYRINTH CHOLLIMA.”

Analysts from Sophos and Volexity has also corroborated this attribution to some degree, with Sophos noting the code was “a byte-to-byte match” with what has been seen in previous activity by the Lazarus Group – the catch-all threat group for DPRK-aligned attackers – and Volexity finding the specific shellcode sequence “appears to have been only used in the ICONIC loader and the APPLEJEUS malware, which is known to be linked to Lazarus.”

Given the wide range of objectives that Labyrinth Chollima – and Lazarus Group, for that matter – have sought to achieve over the years, it’s unclear what their intent was. The fact that the delivered payload was designed to pilfer browsing history from impacted victims indicates that this may have been the first step in a more prolonged, and likely targeted campaign.

How has this been handled?

In six words – very, very, very, unbelievably, cringe-tastically, poorly.

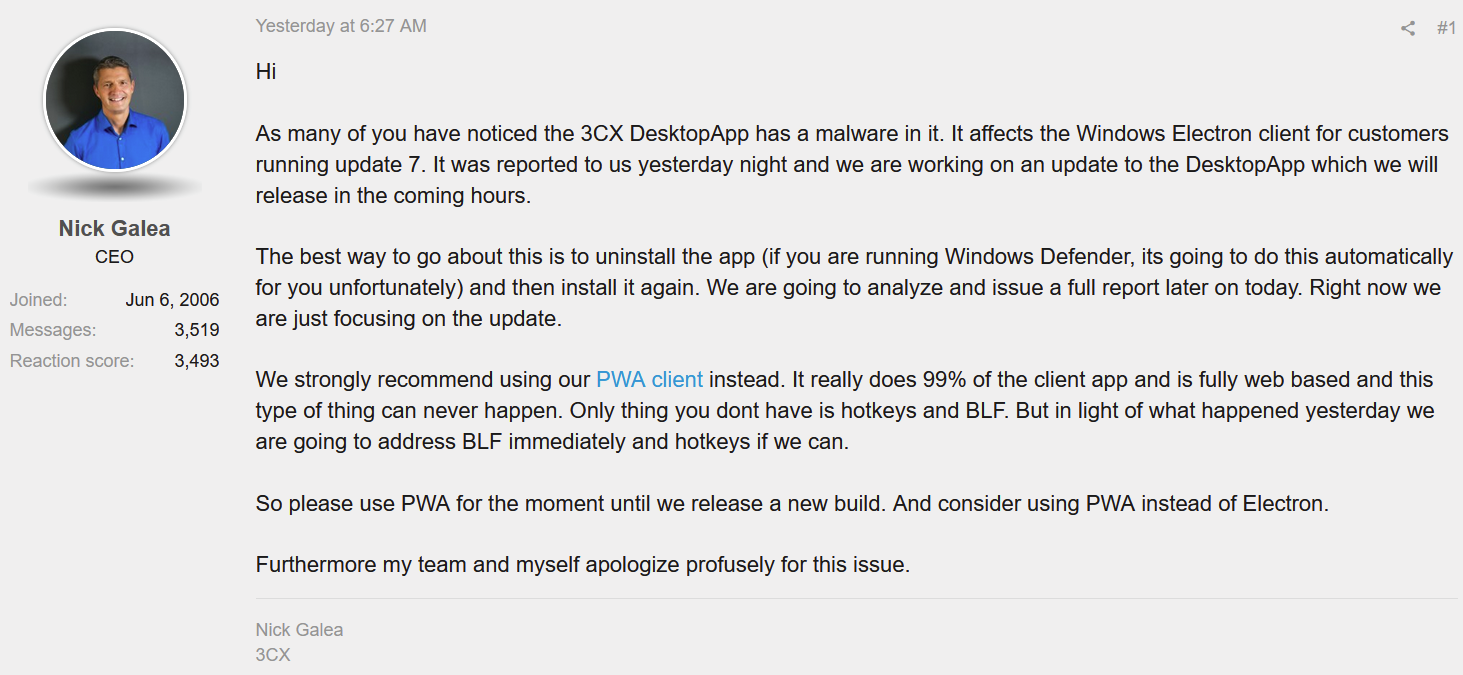

Unfortunately, despite receiving dozens of reports from users of multiple EDR products (SentinelOne, CrowdStrike, ESET, Palo Alto Networks, and SonicWall, to name a few) flagging the VOIP client as malicious, 3CX simply responded by telling customers to add exclusions to allow it to continue to run, and to follow-up with their EDR vendor to resolve the problem.

In an interview with CyberScoop, 3CX CEO Nick Galea noted that antivirus products flagged their software as malicious “quite frequently — so I have to be honest we didn’t take it that seriously […] we did upload it to a site called VirusTotal to check […] and none of the anti-virus engines flagged us of having a virus, so we just left it at that.”

For those wondering what’s wrong with this approach, this Tweet explains succinctly why that is not an adequate validation process for a potential supply chain attack:

So currently expecting a supply chain pwned full installer package that is signed using a cert that is probably whitelisted by not 1-2 vendors to be well detected from the second it was first seen on VT is very very naive, to say it nicely.

(2/2)— MalwareHunterTeam (@malwrhunterteam) 8:55 PM ∙ Mar 31, 2023

If that’s not enough to have your head spinning, cop this – Galea only acknowledged the vulnerability on forums on the 31st of March – more than a week after users began reporting the issue – and claims “it was only reported to [them] yesterday night.”

True to form

A post by respected researcher Kevin Beaumont shows this may be symptomatic of the security culture at 3CX, as he highlighted that when he attempted last year to report a vulnerability that “3CX took little responsibility, didn’t fix it, and started arguing on Twitter”.

The vulnerability? That files – including the admin password – could be read in plaintext.

Leave a Reply