The Great Tariff War of 2025 between the US and China appears to have hit a natural – if unsatisfying – climax, with both parties having skewered the other with 125%+ tariffs, and are now staring at each other, waiting to see which will bleed out first.

Despite this, a quote cited in an article from a few weeks ago has been rattling around in the back of my head, and as overblown as it is – I can’t help but wonder if this is or was a genuine possibility that pundits in our industry are wringing their hands over:

“China will retaliate with systemic cyber attacks as tensions simmer over,” cybersecurity advisor Tom Kellermann told The Register. “The typhoon campaigns have given them a robust foothold within critical infrastructure that will be used to launch destructive attacks. Trade wars were a historical instrument of soft power. Cyber is and will be the modern instrument of choice.”

Turning off water supplies, sewage, or telco networks in retaliation for an (admittedly significant) increase in cost for exports to the US? That seems like a bit much, doesn’t it?

While that quote is alarmist to say the least, I can see this being a legitimate concern for any CEO who’s already worried about the economic impact of this trade war – let alone the Cyber element.

Cyber effects and the norms surrounding them aren’t well understood outside of – let alone within – cyber security, and as practitioners it’ll often be on us to provide that context in cases like these.

So with that said, let’s dissect this, shall we?

Question #1 – Can they do it?

In a nutshell – yes.

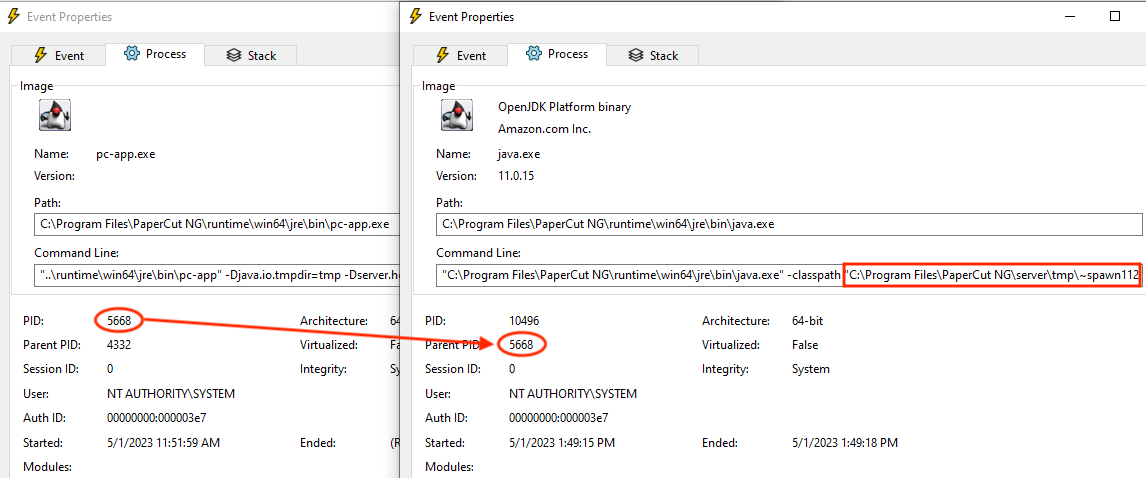

Two well-documented groups with recently observed – and possibly ongoing – access to US Critical Infrastructure are Volt Typhoon, and Salt Typhoon.

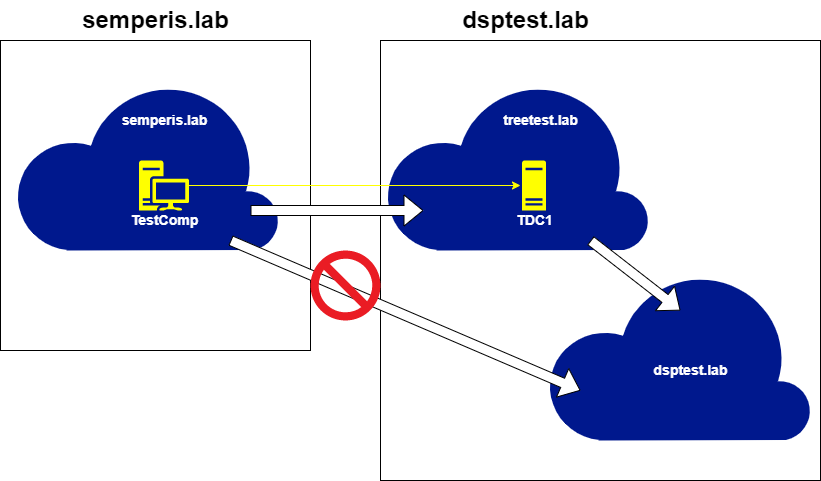

Volt Typhoon was identified as a Chinese government-backed hacking group that maintained access to America’s critical infrastructure – namely systems in the Communications, Energy, Transportation Systems, and Water and Wastewater Systems Sectors – since at least 2021 with the perceived goal of pre-positioning for destructive cyberattacks against these targets.

Salt Typhoon is another highly skilled group that’s been active for at least five years. The group gained infamy after being discovered to have compromised major telcos including Verizon, AT&T, T-Mobile and others; as well as the U.S. Treasury Department. These attacks against Verizon and AT&T are believed to have been carried out as early as 2022, and were only recently uncovered.

It’s also worth noting that Salt Typhoon were found to have compromised the private communications of targeted individuals, including the now-President Donald Trump and his Vice President J.D. Vance. It’s already well known that China has significant Cyber capability, but this is a tangible example of their ability – and appetite – to use it to target whoever they see fit.

Oh, and keep in mind – these are just two of China’s more notorious groups as of late. They also have a mature – albeit disorganised – industry of freelance threat actors they can call on, who “jockey for lucrative government contracts by pledgingevermore devastating and comprehensive access to sensitive information deemed useful by Chinese police, military and intelligence agencies”

Question #2 – Would they do it? How would this even work?

Given that “Cyber” is such a nebulous term that can take many forms and achieve a wide range of impacts, before we can assess the likelihood of it being used – we first need to understand how it could be used.

There are a few noteworthy possibilities to consider here:

Counterintelligence and Espionage

Salt Typhoon’s campaigns have focused on compromising telecommunications networks to collect sensitive data, including – as we mentioned above – that of the current US President and Vice President. If the Signalgate escapade is anything to go by – this may be easier than you’d think, and this level of access would provide China with strategic advantages during trade negotiations.

Expressing Displeasure and Sending Signals

Some have suggested that China could feasibly conduct intrusions with the intent of getting caught – by utilising older tools with a higher risk of detection, for example – to signal their expiring patience in the trade war with the U.S. It might seem like something out of a cheesy Political Thriller, but these “subtle signals” can be a form of communication in a broader “dialogue”.

Applying Pressure in Negotiations

China might use cyberattacks to demonstrate its capabilities and pressure the U.S. to cooperate and negotiate trade.

“China’s methods demonstrate that either the U.S. can cooperate and negotiate trade, or it can impose tariffs and cut legitimate intellectual property transfer and instead be pillaged. The message is essentially, ‘We will get your data no matter what. Do you want to make money off of it or not?’” – Ross Rustici, Cybereason’s Senior Director for Intelligence Services

Legislative Retaliation for Tariffs and Trade Actions

Beijing has clearly signaled that it won’t take this lying down. While they’ve announced tariffs on US imports, some experts believe China could also retaliate through “backdoor” methods using its cybersecurity laws. For example, interpreting the definitions of data localisation, or the concepts of “important data” and “critical information infrastructure” in such a way as to bog American companies in bureaucracy while seeking licenses and approvals to operate in their market.

Question #3 – So, would they actually follow through?

No.

…

Well, sort of. 🤔

To answer it in the context of that original quote – that they would choose to weaponise their “robust foothold within critical infrastructure” in the destructive capacity it’s believed to be intended for – not a chance.

There’s a saying in Chinese – “不要用大炮打蚊子” – which roughly translates to “Don’t use a cannon to kill a mosquito.” It’s essentially saying “Don’t use excessive or complicated measures when a simple solution is available.”

Access to US Critical Infrastructure isn’t something China would leverage to “send a message” in a trade dispute, especially when you consider the likelihood that this is being held “in reserve for a Taiwan crisis”, or something of a similar magnitude. The proverbial “cannon” would likely be better used elsewhere.

More conventional forms of retaliation, such as tariffs, export restrictions on critical minerals, or economic pressure on US allies, are more likely to be employed to solve the problem – and already have been as part of the tit-for-tat.

💡

Speaking of which – reports emerged late last week that Chinese officials had claimed credit for widespread attacks on US infrastructure – including “ports, water utilities, airports and other targets” – as a “warning to the U.S. about Taiwan.”

While this could be interpreted as proof that China would leverage their access to US Critical Infrastructure as a tool in diplomatic disputes, what it really shows is that weaponising this access is simply not necessary for the goals they want to achieve.

To spell it out a bit more clearly:

More Tub-Thumping than a Warning Shot

The tacit warning here is “Hey, pal, we have and will keep pre-positioning in US Critical Infrastructure if you keep insisting Taiwan is an independent country,” not “We’ll pull the trigger and weaponise those accesses if you don’t stop.”

That particular threat isn’t necessary to make their point, and again – that’s something you’d save for a significant crisis, not to apply pressure in a diplomatic discussion.

The Diplomats Who Cried Wolf

China have a less-than-credible history when it comes to messaging on cyber attacks, and frequently deflect attribution as the result of an “overactive imagination” on the US’ part – including calling the Volt Typhoon campaigns a US-fabricated hoax.

My point being – they’ll say whatever is most politically useful for them at the time, regardless of the evidence or facts presented.

* Old Man Shakes Fist At Cloud *

The “indirect and somewhat ambiguous” admission in a secret, closed-doors meeting is an example of what we called out earlier – their use of cyber attacks to “send signals” and exert pressure in negotiations.

Diplomacy – especially for the Chinese Government – is more about posturing than provocation.

That said, Cyber Espionage is a well-worn page in China’s playbook, and it’ll surprise no one to see the likes of Salt Typhoon, for example, being called on to recreate their previous successes by targeting telcos and the communications of America’s leaders. “Knowing is half the battle”, as they say.

An increased tempo of offensive Chinese-backed or enabled Cyber Operations is almost a given in the midst of an escalating trade war that seemingly has come to an uncomfortable stalemate, and the US must be prepared for it.

It’s a good thing the US has a skilled workforce of Cyber Defenders (Oh wait, no they’re shaving CISA’s workforce by 40%), a panel of experts investigating the Salt Typhoon breaches (nope, that was disbanded soon after Trump came into office), and a team of Threat Hunters ready to go (well, what’s left of them).